On 21 July 2022, the European Central Bank (ECB) will put into effect a pre-announced increase in its key interest rates of either 25 or 50 basis points, and will unveil details of a new mechanism to limit widening of euro area sovereign spreads, known as the “antifragmentation” tool. We expect that southern European banks will be the main beneficiaries of both measures.

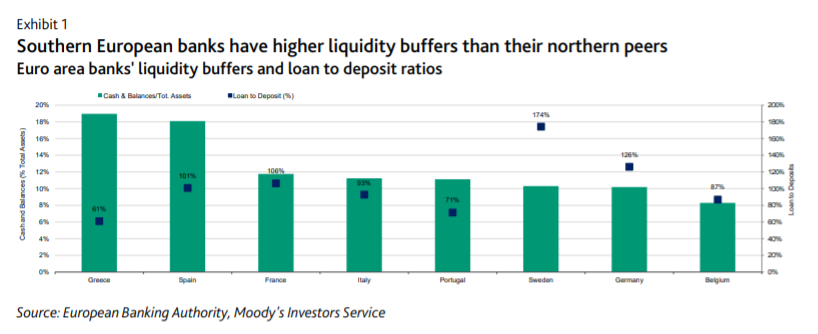

The rate increase will be the euro area’s first in 11 years. The ECB has previously said it will raise rates again in September, and we believe it could follow up with further increases at a later date. Higher interest rates will strongly benefit all European banks’ net interest margins and overall profitability, but the effect will be gradual and will vary between countries. We expect banks in Spain, Italy and Portugal to reap greater rewards than their northern European peers. Since a higher proportion of bank loans in these countries carry variable rates, rising central bank rates will lead to a larger and more pronounced increase in bank revenues. Conversely, the supportive effect on revenue will be more gradual and moderate in banking systems with predominantly fixed rate loans such as France, Germany, Belgium and Sweden. Southern European banks also generally have lower loan-to-deposit ratios and higher liquidity buffers than their northern European counterparts. As a result, they will receive greater revenue benefits from higher yields on their liquid assets, and will not experience material increases in funding costs thanks to their ample deposit bases, which are not highly sensitive to rates movements.

On 21 July, the ECB will also communicate details of its new “anti-fragmentation” tool, designed to limit the widening of sovereign spreads in the euro area. The yield on the sovereign bonds of highly indebted euro area countries such as Italy has risen in recent weeks relative to benchmark German bunds, reflecting concerns over the economic impact of slowing growth and rising inflation.

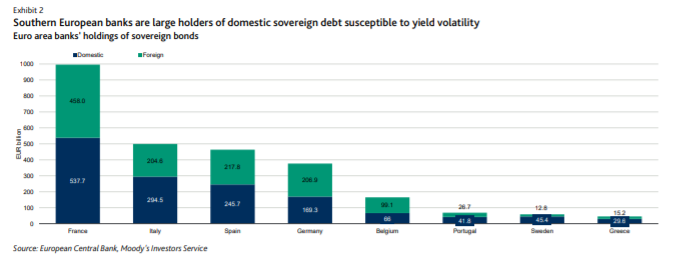

The anti-fragmentation measure will also primarily benefit southern European banks, which hold large volumes of domestic government bonds that are highly susceptible to spread volatility. At end-2021 Italian banks held just below €300 billion of domestic government bonds, while Spanish banks held €246 billion, Portuguese banks €42 billion, and Greek banks €30 billion (Exhibit 2).

The ECB argues that measures to limit rising sovereign spreads – which will likely involve the purchase of government securities – are justified by the need to protect the effective transmission of monetary policy. This is because without such a “transmission protection mechanism”, rising sovereign yields beyond the level warranted by economic fundamentals could prompt higher interest rates for companies and households. This could create distortions that would prevent the central bank from fulfilling its mandate to maintain price stability, and fuel concerns over the financial stability of the euro area.

The ECB is also concerned that the high exposure of banks in some countries to volatile sovereign debt could over time harm their creditworthiness and limit their ability to provide credit to the economy.

This publication does not announce a credit rating action. For any credit ratings referenced in this publication, please see the issuer/deal page on https://ratings.moodys.com for the most updated credit rating action information and rating history.