Moody’s view on what the gas supply rationing scenario would mean for European banking systems. Here are the key research takeaways:

- We identified Hungary, Slovakia, Italy, the Czech Republic, Austria and Germany as the group of countries most susceptible to energy price inflation and possible energy rationing needs over the winter 2022-23. The banking systems in these countries would in an adverse scenario of a complete Russian gas supply cut off (not our base case) face the strongest direct increases in problem loans from loans to the industrial and manufacturing sectors in particular. Knock-on effects will transmit through cross-border supply chains and trade relations into other countries of the EU, so that to a lesser extent, problem loans will also rise beyond the six most affected countries

- EU banking systems confront these challenges to their solvency metrics from a position of strength. Since year-end 2019, just before the start of the coronavirus pandemic, most of the highlighted banking systems have strengthened their loss-absorption capacity through stronger capital buffers, a reduction in problem loans and the creation of stronger loan loss reserve buffers. Under our new baseline scenario of a shallow economic recovery in 2022 and very low growth in the first half of 2023, we consider these buffers needed, but in general satisfactory to absorb upcoming solvency pressures. As an additional safety net, we believe the ECB would consider using its new anti-fragmentation tool in case of outsize pressure on risk premia in a member country.

- In addition to inflationary pressures, the prospect of gas rationing has also dented consumer confidence and, if it materialises, could result in a drop in industrial production and a recession in 2023 that will hurt borrowers and households beyond the direct impact of higher energy costs that public-sector support programs aim to tackle. We expect cost of risk increases in 2022 and 2023 to be more than offset by higher revenue driven by net interest income for most banks; however, we also expect solvency metrics overall to soften from their currently strong levels because of higher problem loans and increases in Risk Weighted Assets.

Energy dependence on Russia, which exposes countries to potential cuts in energy supply and higher energy prices, is a vulnerability for the economies of a number of European nations, and, by extension, their banking systems. Earlier this month, largely based on the countries’ significant energy dependence on Russia, we changed the rating outlooks for several Italian, Czech and Slovakian banks to negative, mirroring outlook changes to negative for the corresponding sovereign ratings1. It is uncertain whether Russian energy supply to

Europe over the winter of 2022-23 will be high enough to avoid gas rationing measures in EU member states. Earlier, we also lowered our baseline macroeconomic forecasts for several EU economies, in large part to reflect unsteady energy supply.

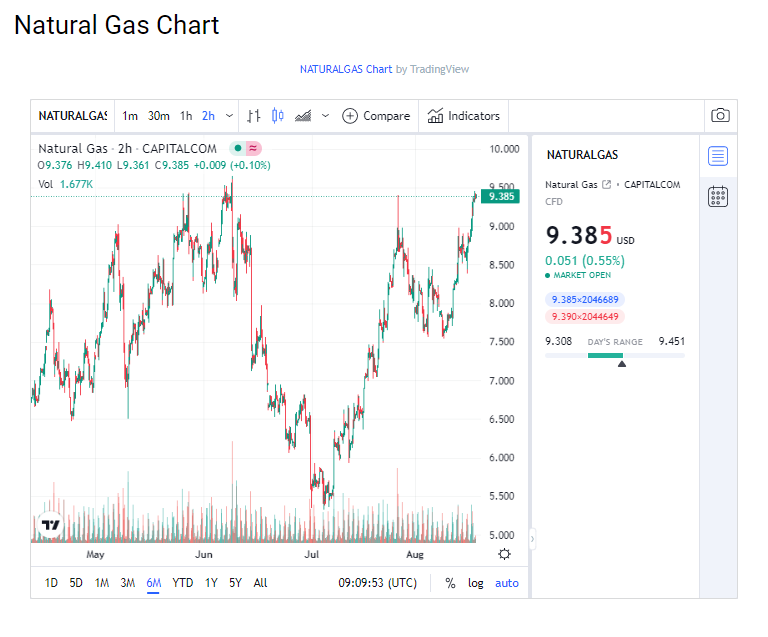

See here the Natural Gas Live Prices Chart.

Six European economies are most exposed to Russian gas.

We identified Hungary (Baa2 stable), Slovakia (A2 negative), Italy (Baa3 negative), the Czech Republic (Aa3 negative), Austria (Aa1 stable) and Germany (Aaa stable) as the countries most susceptible to energy price inflation and possible energy rationing needs over the winter 2022-23. In an adverse scenario (not our base case) of a complete cutoff of Russian gas supply, the banking systems in these countries would be the first to experience increases in problem loans and riskweighted assets from exposures to the industrial and manufacturing sectors in particular. Knock-on effects would transmit through cross-border supply chains and trade relations into other countries of the EU, so that problem loans would also rise beyond the six most affected countries, although to a lesser degree.

European banking systems have solid loss absorption buffers.

The six most exposed banking systems continue to possess strong loss-absorption buffers, which they even strengthened from the high level before the pandemic. Similarly, borrowers have strengthened balance sheets and household finances during a long positive credit cycle, and forceful government support measures during the pandemic have prevented lasting damage to the creditworthiness of the private sector.

Risks to solvency could rise despite European governments’ support for economies.

The European Central Bank (ECB), and even more so its Czech and Hungarian peers, have raised rates to rein in inflation, which, in combination with recent increases in public sector debt, somewhat limits authorities’ flexibility to provide fresh monetary or fiscal support. In several countries, burden shifting among the economic sectors has been detrimental for domestic banks, which have been confronted with borrower-friendly moratoriums or windfall taxes.